In the far northwest of Australia, Exmouth Gulf is a sanctuary for humpback whales, dugongs and turtles, a blue-carbon reservoir in a breathtaking landscape like no other on Earth. But all that could change, as developers push ahead with potentially tragic consequences. Tim Winton is one of those fighting to preserve this wonderland.

I hustle down the red-dirt track with my board and paddle, winding through the spinifex, and although I can’t even see the water yet, the huff and slam of gigantic bodies feels so close I’m tingling with excitement.

I crest the dune, hotfoot it across the rocky beach, and when I hit the water, I disturb a gang of baby blacktip sharks who set off a starburst of sand as they streak away across the shallows.

Then I’m paddling for the drop-off, where a colossal creature bursts from the water. It hangs airborne for a moment, black and shining in the sun. Flexing its spine, cranking its pecs. And when it slams back down it sets off such a mighty thump and welter of spray, you’d swear a bomb’s gone off. Up comes another. Then a third. It’s pandemonium out there.

Whale season at Ningaloo. Every winter humpbacks stream north, right against our western coral reef, where the oceanic deep suddenly meets the desert. They come from Antarctica in their thousands, in convoys stretching fore and aft over the horizon. But Ningaloo Reef is not their final destination. They’re headed for sheltered bays and estuaries inshore, where it’s safe and quiet enough for them to rest and nurse their calves.

Exmouth Gulf is one of those havens. We call it Ningaloo’s nursery. And this is where I am today, in one of the most significant humpback refuges in the world. When I was a kid there were only 300 humpbacks left on this side of the continent. Now, thanks to conservation efforts, there are about 33,000. I’ve been watching this recovering population for decades, and the sight and sound of them still inspires me. But even in the midst of whale-watching at Ningaloo, you can become distracted – by unexpected events, different creatures. Like a posse of partying dolphins. A tiger shark as big as a boat. Or a marlin that surfaces silently beside you to dish out a bit of side-eye. At Ningaloo’s nursery you just never know what you’ll encounter – that’s how rich and wild it is.

Today turns out to be a case in point. As I reach deeper water, the whales dive in unison and everything goes quiet. So I stop and wait, watching for where they’ll surface next. And in the long lull, I hear a tiny puff behind me. Not the big-bore blow of a whale. Just a discreet little…poot.

I chuck a U-turn immediately. Because I know that sound.

I paddle back gently into the shallows. And there they are. Dugongs. Four of them. Mothers with calves. The adults are nearly three metres long and probably weigh over 300kg. Tawny and narrow-shouldered, with broad tails like dolphins, dugongs don’t have a single spiracle or blowhole like dolphins or whales – they have paired nostrils, like us. Which must be the only reason sailors could have once mistaken them for mermaids. Because although they are lovely, slim-hipped creatures, with tiny, curious eyes and a placid disposition, they’ve got a face that only a mother could love. And they have truly awful breath. Just saying!

I pull up at a discreet distance and sit on my board to watch them graze. Despite all my diligent back-paddling, the tide carries me closer until I’m certain they’ll startle and swim off. But they pay no attention. Which is unusual because they’re notoriously shy. They carry on munching contentedly, their blunt snouts in the seagrass. I’m happy to sit and watch for as long as they’ll allow me.

These animals belong to one of the last large and stable populations of dugongs left in the world. Ningaloo is a haven for the species. And while watching them forage is a treat at any time, this year it feels particularly special, because 2021 marks the 10th anniversary of Ningaloo being added to the World Heritage list. For those who’ve spent decades fighting for the place, this is more than a historic milestone. It’s a personal reminder of how, against all odds, citizens can unite to create change for the better. And this is something I’m proud to have been a part of.

But it’s a bittersweet anniversary. Especially as I gaze down at these dugongs today. Because although Exmouth Gulf is one of the last global refuges for these creatures, this crucial bit of Ningaloo is not part of the World Heritage Area.

It was supposed to be. In 2011, when the World Heritage boundaries were being determined, the IUCN, which advises UNESCO, was clear about the Gulf’s values. And because the scientific case was compelling, it was included in the original “optimal” boundary. But the local shire opposed all World Heritage listing at Ningaloo. The Chamber of Commerce was so hostile it sent a representative to Paris to try to speak against it. In the end, the Ningaloo listing was successful, but despite the science, Exmouth Gulf was excised.

As a result, Ningaloo’s nursery remains wide open to industrialisation. Which is a perverse anomaly, but that seems to be what opponents of World Heritage had in mind. So every year developers arrive with new proposals to try to kick off the carve‑up, and year upon year, Ningaloo’s defenders have to fight to keep the nursery safe. Like any siege, it’s exhausting, and costly. It’s heartbreaking as well. Because it shouldn’t be necessary.

Thus far, thanks to community pressure, the Gulf has been spared. Petroleum tenements came to nothing. A saltworks was seen off. A supply base for the fossil fuel industry was rejected. Last year, after an overwhelming public outcry, the Gulf was saved from a subsea pipeline facility.

But this year it faces something even worse – a deep-water port for heavy shipping. And once again, Ningaloo’s battle-weary champions must find time and resources enough to defend it. As ever, it’s an unequal contest.

I’ve been visiting, studying and defending Ningaloo for half my life. It’s been a source of intense pleasure and inspiration. So when I was commissioned in 2020 to write and present a three‑part TV documentary for the ABC about the place, I saw it as a once-in-a-generation opportunity. But also as a personal obligation. And while our work-in-progress is meant to be a celebration of one of the world’s last great sanctuaries of biodiversity, I’m aware that I could be left presenting a eulogy instead. Because this year Ningaloo is on a knife-edge. It’s touted as one of Australia’s finest conservation successes, and rightly so. But a decade after World Heritage listing, its future is in jeopardy. And it sickens me to think I could be left writing its epitaph.

Ningaloo consists of three interconnected ecosystems – the Reef, the Range and the Gulf. They’re treasured by scientists and adored by tourists because together all three places offer natural experiences and events you can’t get anywhere else. Here, within a single day, you can swim with a whale shark, a humpback whale, a manta ray, a turtle and God’s own acid-trip of brightly coloured reef fish. And if you’ve got any vim left afterwards, you can hike the gorges, go birdwatching in the mangroves, do some caving in the canyons and then surf until sunset.

If you haven’t been there, picture this. It’s isolated – a remote peninsula 300km long. Arid. Red dirt, spinifex, very few trees. And no agriculture – so no coral-smothering run-off. Along the spine of this great cape is a rugged series of ranges. Canyons and creeks carve meandering paths across the coastal plain. On the western edge, the world’s longest nearshore coral reef. So close that in places you can wade to it. And on the eastern shore, Exmouth Gulf, one of the largest intact arid-zone estuaries left in the world.

All three Ningaloo ecosystems are outstanding. The Cape Range contains a breathtaking cave system with subterranean waterways full of rare and ancient stygofauna. The Reef, of course, has its famous whale sharks, corals and manta rays. It also supports 500 species of fish. Exmouth Gulf is a nursery for prawns and crabs and critically endangered sawfish. It’s a global hotspot for sea snakes, and along with its massive mangrove forests, its sponges, seagrasses and corals, it’s a refuge for marine mammals.

Just to the north of Ningaloo lies the Pilbara where it seems almost every major coastal landscape and waterway has been industrialised already. That’s where all the gas hubs and industrial ports are, where lands and waters are dominated by infrastructure – oil rigs, tankers, ore trains, bulk carriers and terminals. So, regionally, the Ningaloo coast is unusual, an exception to the rule. The Reef has been deliberately spared. By governments responding to scientific advice and public concern. This is despite relentless pressure from developers, diggers and dealers.

The natural values of the Ningaloo region are remarkable and irreplaceable. And in a world where such places are vanishingly rare, its social value is exceptional. Locals understand this. So do the tourists and scientists who travel so far to visit. The local economy is underpinned by eco-tourism, which is well managed. Like the ecosystems that make it possible, the Ningaloo “brand” is top shelf.

But Ningaloo is at a critical turning point. Because although two of its ecosystems are largely protected, the third is now in imminent danger of being industrialised. And that puts the whole place – its environmental integrity and its sustainable economy – at risk.

A start-up called Gascoyne Gateway Limited wants to build an industrial deep-water shipping facility at the northern end of Pebble Beach, which is about 30km into Exmouth Gulf. GGL’s proposal includes a large fuel depot to refuel ships of up to 250m, and a 900m wharf jutting into the estuary. This is a big, hard chunk of kit to impose on a whale refuge and dugong habitat. It means dredging over a million cubic metres of seabed – and that’s just in the construction phase. Given it’s a 100-year piece of infrastructure, a century of maintenance dredging can be expected. In a blue‑carbon reservoir. With 2050’s global climate target less than 29 years away.

Because this privately run port is designed to attract heavy shipping and must draw in more and larger ships to pay its way, it’ll serve as an industrial intensifier. It promises to be, as the name suggests, a gateway to industrialisation. And a beginning of the end for the Gulf. For already, other proposals are targeting the tidal flats of its wetlands – a saltworks by K+S Salt, and a sulphate of potash operation from Wyloo Metals. Decisions made this year are likely to determine the Gulf’s fate.

Sustainable tourism at Ningaloo depends on pristine ecosystems and on creatures that are safe and contented. Which is why tourism operators, residents and visitors are alarmed by industrialisation in general and this deep-water port proposal in particular. And why so many marine scientists and conservationists share their concerns. Because an industrial port here would be a game‑changer. Marine mammals require space. They need quiet. Heavy shipping colonises and dominates waterways and generates huge noise. So in a whale and dugong refuge, the prospect of more industrial traffic, more light, higher risk of boat-strikes and spills and marine pests, is really ugly. When you consider the dredging, the pile-driving and the smothering rubble required to build a 900m wharf, it’s uglier still. The idea is so incompatible it’s hard to believe anyone would even suggest it.

Ningaloo’s corals are yet to experience the widespread catastrophic bleaching events seen at the Great Barrier Reef. Compared to ecosystems elsewhere, the Reef, the Range and the Gulf are in enviable shape. But all three are fragile and vulnerable. The direct threats posed by GGL’s port are obvious and unacceptable. But there’s a broader existential threat to consider.

Exmouth Gulf is a massive natural carbon sink. If spared industrialisation and properly protected, it can help mitigate global heating. But it’s besieged by industries seeking to exploit it, including those that threaten the very existence of Ningaloo Reef and all the world’s corals. Some of our nation’s biggest carbon polluters continue to operate just offshore. And instead of winding back for a transition to safer, cleaner forms of energy, they’re doubling down, with government support, to get what they can while they can.

That’s why there’s still an incentive for speculators, why, even in 2021, developers are still trying to build allied industrial infrastructure onshore – here in Ningaloo’s nursery – to prop up some of the very industries most likely to destroy Ningaloo Reef.

For a billion urgent reasons, for the sake of our children’s children, this madness has to stop.

I’ve been lucky enough to see dugongs gather in their hundreds here in Exmouth Gulf. But even the little band I’ve come upon today is something to savour and marvel at. Because these animals are a signal of health and a source of hope. But like the grand and fragile ecosystem that supports them, they need to be defended against industrialisation. Their habitat needs protection. We must end this perpetual siege, and secure one of the world’s exceptional places once and for all.

I don’t want to end up being Ningaloo’s public mourner. I’m determined to celebrate its glory and rejoice in its survival. Because there’s nowhere else like it.

Getting Ningaloo added to the World Heritage list took the work and the voices of thousands. Securing Ningaloo’s nursery will require many more, but I believe that after all these years, sense will prevail: we’ll finish the job and see Exmouth Gulf included. I want to paddle out one day to mark that anniversary.

Tim Winton is the author of 29 books. Named a National Living Treasure in 1997, he is the patron of the Australian Marine Conservation Society. His stunning documentary Ningaloo Nyinggulu is now on ABC iview.

Photos by Violeta J. Brosig

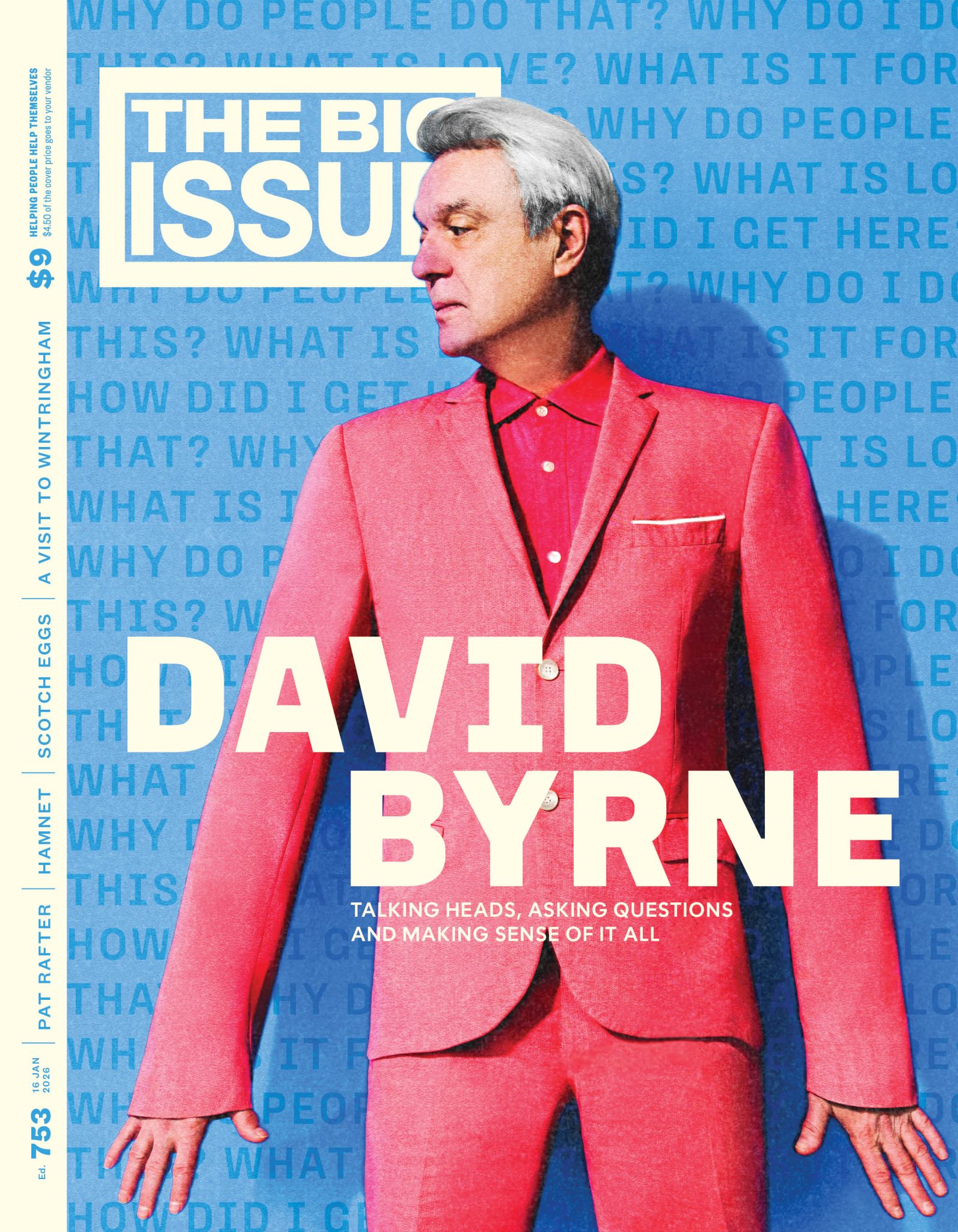

This story was originally published in Ed#644 of The Big Issue